Creating a built environment on a human scale

In 1984 HRH Charles, the Prince of Wales, gave a speech that shook Britain’s architectural community to its foundations. In a speech to the Royal Institute of British Architects, Prince Charles said that a proposed addition to the National Gallery on Trafalgar Square looked like “a kind of municipal fire station, complete with the sort of tower that contains the siren…a monstrous carbuncle on the face of a much loved and elegant friend.”

The American architectural critic Nikos Salingaros says the prince was “crucified by the architectural press, and the architectural establishment launched an all-out campaign to discredit him.” By 1998, as the fashion for plainness gave way to more flamboyant structures, Charles wrote about “the brash megalomania which sometimes masquerades as creative design.” Years later the attacks go on, and the Prince for his part returns them tit for tat, sometimes with pithy humor that the press loves to quote. He told London’s urban planners: “You have to give this much to the Luftwaffe. When it knocked down our buildings, it didn’t replace them with anything more offensive than rubble….Around St Paul’s, planning turned out to be the continuation of war by other means.” He accused London’s architects and developers of treating their city “as merely a financial staging post between New York and Tokyo.”

While Charles’ flamboyant statements employ a lot of ink, they are only a small part of his architectural philosophy. Indeed, this untrained amateur has developed a coherent and detailed critique of modernist architecture and urban planning that includes an alternative approach to replace it: his famous Ten Principles. Nor has the Prince of Wales been content to issue manifestos; he has put his considerable fortune where his mouth is, founding an architectural institute (The Prince’s Foundation for the Built Environment) and creating a land development meant to epitomize his theories. That development is Poundbury, in the small Dorset county town of Dorchester.

One of Britain’s most pleasant market towns, Dorchester sits in the middle of Dorset’s famed Hardy Country, a compact oval barely larger than 2 square miles that contains 16,000 people. A densely packed High Street, built along a Roman road, forms its center, framed by the lovely little River Frome on its north and an 18th-century tree-lined parade on its south. Deeply rural lands surround Dorchester on all sides, comprising a rolling landscape made famous by the 19th-century novelist Thomas Hardy: thatched villages, narrow lanes, walled fields, grassy moors, Celtic hill forts and Roman ruins. Not remarkably, tourism is Dorchester’s largest employer after government and health services. It is certainly urban with its tiny area and large population, but no one would describe it as a city, and it is by no means a high-growth center.

[caption id="PrinceCharlesPoundbury_img1" align="aligncenter" width="719"]

Jim Hargan

Like other British towns, planning regulations have long kept Dorchester from sprawling out into the countryside. Up until 1990, planners had kept Dorchester confined to a bit more than 1 square mile; there was only one major tract that qualified for new development, a farm on the western edge of town, and that was firmly locked up as part of the Duchy of Cornwall. As it happens, Prince Charles is the Duke of Cornwall. In 1991 Charles decided to open this Poundbury Farm tract to development—his way. Dorchester’s new subdivision of Poundbury was to follow the Prince’s Principles (see sidebar, “Somewhere Between Ten and Fifteen Principles”) and show that new development could be as graceful, attractive and livable as older neighborhoods. Fifteen years later, the results are remarkable.

Neither the Prince nor his opponents are operating in a vacuum; a rich and complex history has led to their confrontation at Poundbury. Before Roman times, the native Celtic Britons lived in dispersed farmsteads, “protected” by a ruling class that lived in earth-banked hilltop forts; the largest surviving hill fort, Maiden Castle, is less than a mile from Poundbury. The hill forts emptied with the end of the Roman occupation, to be replaced with carefully planned civitates, walled towns eventually built of stone, where the old ruling class now donned togas and met in the Roman baths; everyone else continued to live in dispersed farmsteads. The Saxon conquest of Britain (AD 450 to 600) destroyed Roman civilization and town planning, while the rural population remained dispersed. Then, around 880, King Alfred the Great established a new phase of carefully planned urban development with his system of burghs, walled towns that provided protection from raiders, planned crop management and markets for goods. Dorchester was one of the original burghs behind its stone Roman walls, and burgh-like villages surround it to this day.

The result was a controlled free market in land,with architectural harmony imposed in such a way as to allow a good deal of variation

Intentional, centralized urban planning resumed piecemeal in the 18th century, then became a major obsession in the 19th century. England’s 18th-century planning was done by private developers who controlled large tracts on the edge of boroughs. They used wealth from the Industrial Revolution to construct urban areas that reflected the values of the newly moneyed classes—places that were serene, beautiful, functional and pleasant. Terraces of white classical townhouses would face country views in sweeping circles, or lead into rebuilt markets on wide new streets cut into the old Alfredian boroughs. Typically a major developer would plan out the project and install the infrastructure, then continue as the “ground landlord,” the actual landowner. He would then lease subtracts to smaller developers, regulating what they built. The result was a controlled free market in land within the project, with architectural harmony imposed in such a way as to allow a great deal of variation. This is the method, and much of the philosophy, behind Poundbury’s construction.

[caption id="PrinceCharlesPoundbury_img2" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

Jim Hargan

By the early 19th century, the Industrial Revolution had shifted into high gear, and major cities acquired factories built on a scale unseen since the great cathedrals of five centuries earlier. With massive population growth and nearly no municipal government, these cities were a mess. The turnaround began in 1835, when a reform act created powerful, elected governments for nearly every city and town, and the new municipal governments started a mad scramble to fix the problems. One by one they obtained acts of Parliament allowing them to seize privately owned sewer, water and gas systems. They imposed careful planning on their new assets, unifying the hodgepodge of private systems, extending them to the poorest areas, separating the sewage and drainage systems from the water systems, and imposing health and sanitation codes on both new buildings and old. By 1920 cities were basically safe and healthier places (except for coal fumes from household fires, a major health hazard not addressed until the 1950s). This great cleansing made up the third phase of urban planning—a planning effort that was comprehensive and successful, even though it did not include zoning or other land use regulation. Zoning had to wait until the 20th century, and the philosophy of Ebenezer Howard.

At its heart, Prince Charles’ approach is environmentalist, not traditionalist—with the advantages of a mature and stable ecology

Ebenezer Howard was no one in particular—a mousy little clerk in late 19th-century London—until he published his concept of the “Garden City” in 1898. Like nearly everyone else in his era, Howard had little historic perspective on the rapid improvement of cities; he just assumed that cities were irredeemably bad and getting worse. He “invented” (his term) a new type of settlement that he thought could replace cities altogether, producing the same amount of goods and services while allowing everyone to live in a bright, clean environment surrounded by nature—a community he called the “Garden City.” Although Howard addressed all aspects of urban life and economy, only his ideas on physical layout made it into 20th-century planning practice. Howard proposed segregating land uses into zones that would separate the incompatible areas and better organize the economy; he also mandated low densities and plenty of greenery. In fact, the modern density-regulating zoning code derives from Howard.

Howard gave us the technical tools of modern urban planning; Le Corbusier contributed the theory. A Swiss watch engraver turned Parisian intellectual, Le Corbusier obsessed over giant skyscrapers surrounded by parkland. The exact nature of these emparked towers would evolve with his politics (which ranged from industrial elitist in the 1920s to Vichy Fascist in the 1940s) but the basic format remained the same. Each huge skyscraper would house an entire city, from residences to shops to places of work. The social elites would occupy luxury flats on the top floors, while workers would be housed in modestly adequate apartments farther down. Wide parklands would separate the towers; a group of such towers would make up a great city. Le Corbusier presented these towers as symbolizing the triumph of the Machine over Humanity, of the Collective over the Individual. You can see his emparked towers all over America and Europe, often miserably dysfunctional places—but his symbolism had the deeper influence, and informs every modernist construction project.

Jim Hargan

Oddly enough, Le Corbusier’s modernism is commonly seen as progressive, the opposite of a Tory traditionalism that wants to return to a class-bound past. But what a peculiar type of progress it is! Technology triumphs over Nature; buildings are machines; people in buildings are pieces of the machines; elites ensconced in top-floor luxury suites push all the levers on the machines. This is a progressive nightmare. And that, of course, is the point of Poundbury. At its heart, Prince Charles’ approach is environmentalist, not traditionalist. With his Principles, Prince Charles is looking for a way to create a built environment that duplicates the advantages of a mature and stable ecology, a livable environment that is harmonious and egalitarian.

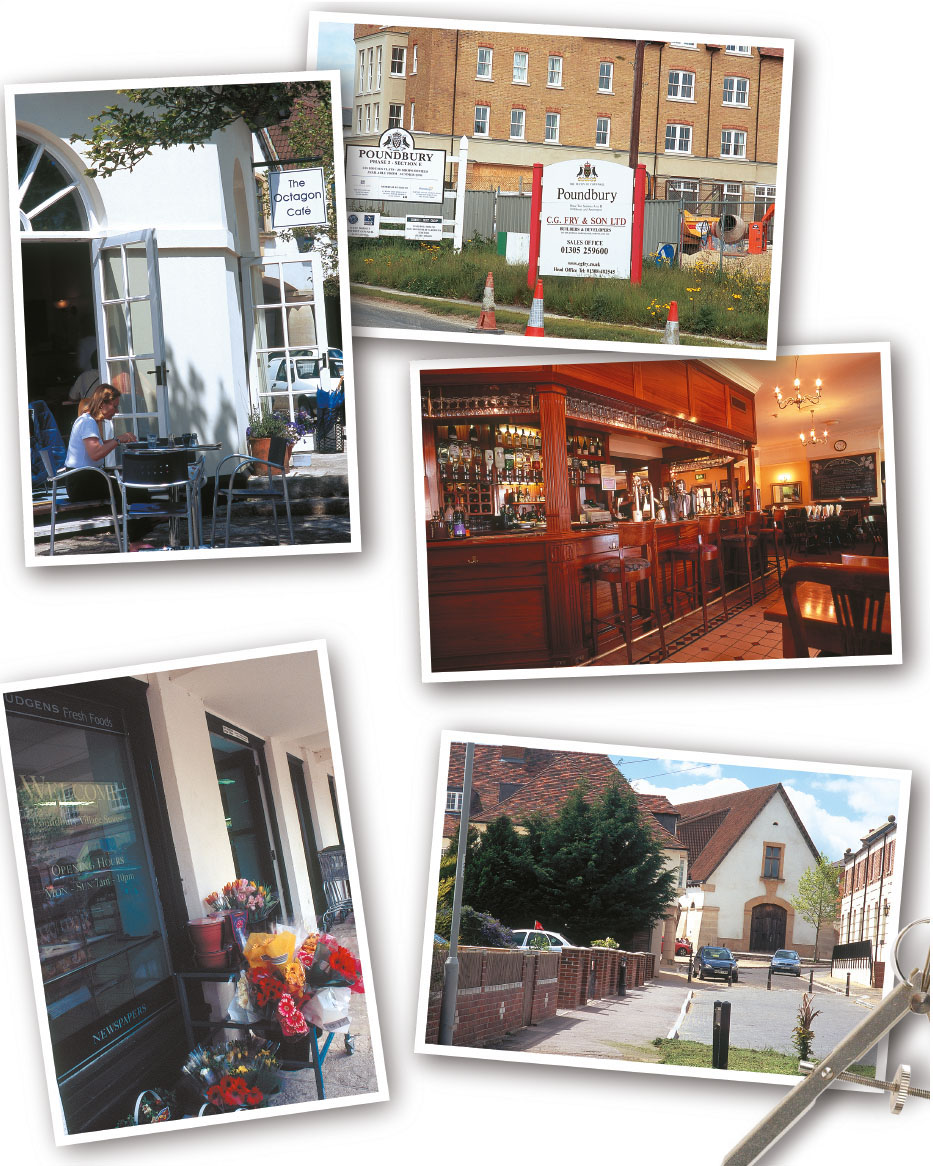

Poundbury starts as a village, a tightly packed center of mixed architecture and uses. Its well-defined center, removed from the noisy main road, has a market square with a guildhall raised on bulbous columns above an open piazza, a small grocery store, a very nice pub and several shops. Both the pub and a tea shop provide outdoor seating on sunny days, and the square is invariably mobbed. Narrow streets radiate chaotically, and some appear to be unpaved (they’re not); the planners actually laid out the building lots, then fitted the streets in between them, so the lanes tend to make random jerks. There are no parking restrictions anywhere, although all residents have cleverly hidden off-street parking. Like the great 18th-century projects, the developers that act for Prince Charles have established rules that impose a common that act for Prince Charles have established rules that impose a common architectural language while allowing individuals a great deal of freedom in designing their own buildings. It is visually engaging and just a little bit over the top—a lively, happy jumble, filled with people.

[caption id="PrinceCharlesPoundbury_img4" align="aligncenter" width="933"]

Jim Hargan

[caption id="PrinceCharlesPoundbury_img5" align="aligncenter" width="944"]

Jim Hargan

Needless to say, the modernists hate it. “Pastiche,” they call it—a cluttered mixture or hodgepodge. In the modernist world, a lively street life, functioning neighborhood shops and happy residents are symbols of a bourgeois Tory longing for an impossible past in which there are no poor. Actually, there are plenty of poor in Poundbury, more than in Dorchester as a whole; 25 percent of the units are affordable, rent-subsidized housing. No one will tell you which specific units are earmarked for the poor—it’s a secret—and you certainly can’t tell by looking. The poor and the well-off live together without that distinction.

To the casual visitor, three views define the Poundbury village core. From Dorchester’s center on the main highway, the foremost view consists of two very large buildings: an apartment complex fashioned like a French villa and an assisted living facility that resembles a modernist interpretation of a castle. This is the part most visible, and that attracts the most criticism as “pastiche.” Both buildings are functional, however, forming a gateway and a screen. Behind them are the intimate residential lanes of Poundbury, protected by their bulk from road noise and fumes.

If instead you approach Poundbury using Cambridge Road—a normal, modern suburban road—you’ll experience a much more dramatic view. After a half-mile of driving down a straight, wide road lined by dull, lookalike brick semidetached homes, you suddenly run into a tightly-packed chaos of competing rooflines and styles, with pillars, stone, plaster and brick in a fight for attention in which the market hall is the clear victor. Here you must stop and walk, for Cambridge Road is blocked from entering Poundbury’s village center. This brings us to the second-most common criticism, of “Disney World”—as if it’s a moral shortcoming to prefer a lively, beautiful neighborhood over a spirit-quashingly dull one.

Somewhere Between Ten and Fifteen Principles

In 1989 Prince Charles published his famous Ten Principles for planning the built environment. Since then, his Foundation for the Built Environment has dropped two and added five, for a current total of Thirteen Principles.

Eight Principles From the 1989 List:

- The Place: Designs should recognize the things that make a locale unique; blandly anonymous development is bad.

- Hierarchy: A building’s physical presence should reflect both its function and its importance.

- Scale: Buildings should relate to the scale of the people who use it; a building and its spaces should not overwhelm or alienate.

- Harmony: A building should be individual, yet should act as part of its surroundings.

- Enclosure: Public and private spaces should be clearly delineated, as should urban and rural spaces.

- Materials: Designs should incorporate indigenous materials that blend with the landscape and improve with age.

- Decoration: Designs should incorporate decoration from artists and fine crafters.

- Community: The existing community should be involved in all stages of design.

Five Principles Since Added:

- Public Space: A building’s public areas, including signage, lighting and street furniture, should be as carefully designed as the rest of the project.

- Permeability: Blocks of buildings should be easily penetrated, allowing free movement of people and goods.

- Longevity: Buildings should be constructed in such a way as to be long-lived, including adaptability to new uses after original uses have ceased.

- Value: The design of the building should increase its value as an economic asset.

- Craftsmanship: A building should exhibit good craftsmanship in its construction.

Two Concepts Dropped From the Original List:

- Art: Public spaces should display original art that is relevant to the community.

- Signs and Lights: These should be an integral part of the design.

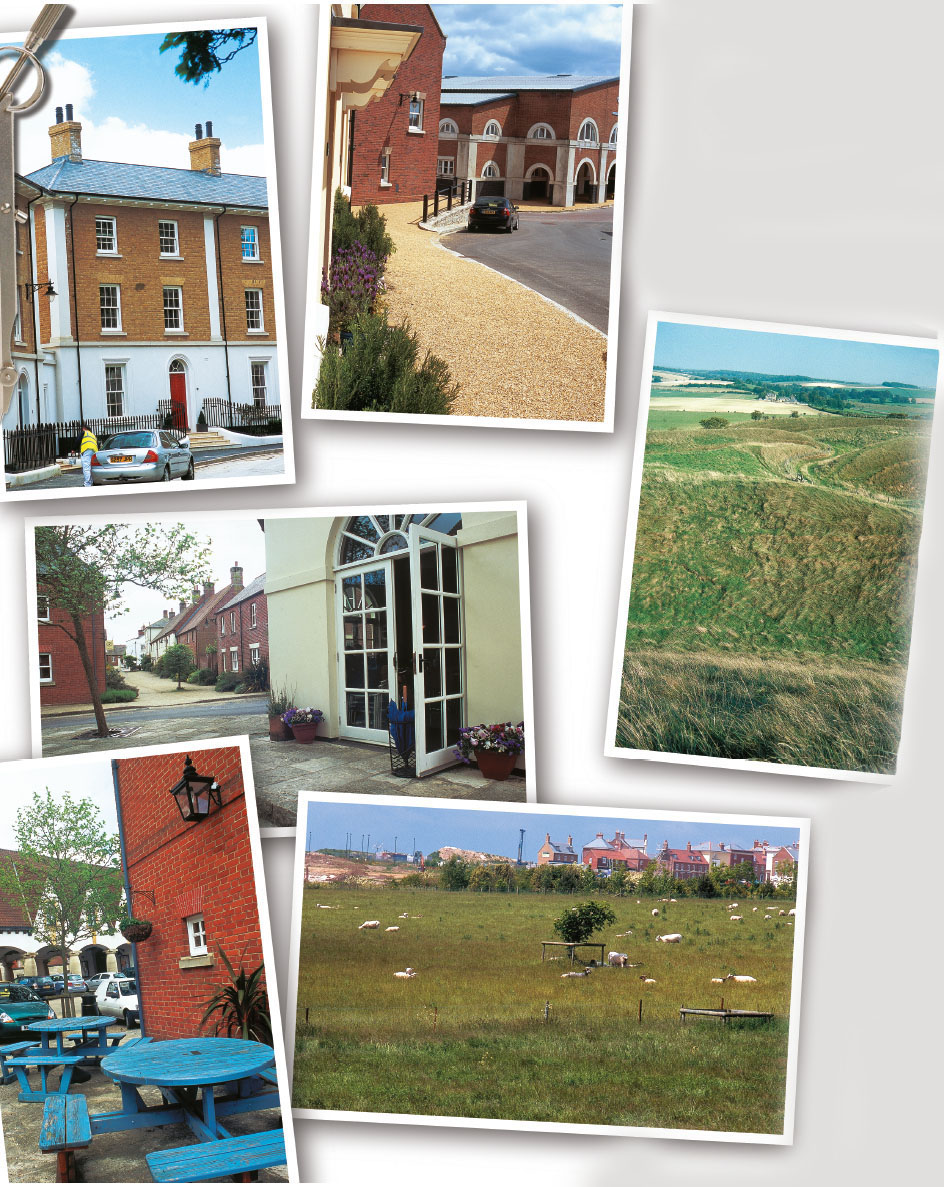

The third view is from the village’s southern edge, along a curving hilltop. Here its recreational lands give wide vistas toward the gigantic form of Maiden Castle, the Iron Age’s premier example of urban planning. From the Poundbury playing fields, a paved footpath leads in the direction of the castle. Look back, and Poundbury’s southern front has been modeled after an 18th-century curved crescent whose terraces looked over the countryside.

Yes, an Anglo-modern village set in the midst of red brick suburbs does look a little odd. Or it did—for Poundbury is now expanding, roaring into the second of three phases and tripling its size. The new phase is being developed in Georgian classical styles, with wider streets leading up from the crazy lanes of the village core, and it is beginning to gain the same sort of organic harmony of an ancient market town. The main highway that splits the Poundbury project is being returned to its former function as a fine old Roman road. A new neighborhood center has already opened on the Roman road, with an amazing statue of buxom young mermaids splashing about in a fountain. A goodish sized factory is integrated into the fabric, its Georgian front facing the residences and its loading docks facing outward, away from the project. This, along with the neighborhood centers, illustrates one of the Prince’s main breaks with Howard: an insistence on a rich mix of uses, instead of stiffly segregated zones.

Despite Dorchester’s remoteness and slow population growth, Poundbury’s large second phase is building out quickly. The developers say that you will not be able to judge its success until the third phase is complete—and they are keeping details of that under wraps for now. However it turns out, it’s clear that the planning ideas in Poundbury are a serious challenge to the blandly impersonal modernist developments that all too perfectly capture the spirit of a machine-dominated age.

Comments